Fear of Failure: What it Means for All of Us

20 min read

Photo by Edu Lauton on Unsplash

300.000 years ago, a man was leaving his cave to hunt for food. It was an extremely harsh winter and finding food was harder than ever before. On a recent trip his brother got mauled to death by a saber-toothed cat, and since then he was terrified by the mere possibility of meeting one of those beasts again. He had nightmares where he left the cave in search for food, only to come back and witness the cat devour his family.

This fear was constantly in the back of his mind every time he went hunting. He always hesitated with the decision. Should he go hunting now when the snow storm has calmed down? Or should he search the area around for any predators to make sure that his family will be safe, and in doing so losing precious time before another storm?

This fear has made him cautious and vigilant. But at the same time it has made him hesitant and passive. One could argue that this fear of failure was the mechanism that would keep him alive, but another would say that this fear made him less of an adventurer — potentially missing out on a better hunting area and better food, as his nomadic instincts were suddenly suppressed since that encounter with the wild animal.

A few tens of thousands years later, Neanderthals — the more sedentary and physically stronger species — were on the brink of extinction, while Homo Sapiens — the more nomadic and “brainier” type — were flourishing.

The reasons for the Neanderthal’s extinction are still largely unclear, but there’s some arguments that their less adaptable nature made them more vulnerable to climate change and natural disasters, meaning that they tended to stick to the same geographical areas when trouble hit them, rather than travel as much as Homo Sapiens.

Or maaaaybe it was just pure bad luck and Neanderthals got f*cked over when around 40.000 years ago, a sequence of 3 major volcanic eruptions devastated Neanderthal homelands in Europe and Asia.

Yeah, maaaaybe.

Or maybe if they WEREN’T SO F*CKING DUMB AS TO SETTLE RIGHT BY THE VOLCANOES YOU KNOW LIKE THE THING THAT SPITS LAVA ON YOUR ASS, maybe then they wouldn’t be so DEAD.

I mean, being brave is cool and all but YOU CAN’T FLEX YOUR MUSCLES IN FRONT OF A VOLCANO IT DOESN’T CARE DUDE STOP.

Okay, anyways, back to the topic.

The fear of failure is as much a powerful motivator as it’s a devastating obstacle to action. It’s the boogeyman that follows you anywhere you go. The throat lump you get when you have to speak in front of an audience. The hesitation to approach that beautiful person that caught your eye. The whirling and sickening motion of your thoughts that spin like a broken ceiling fan in an abandoned room where no one’s living.

Yes, we read about the human mind and we find out that fear is an illusion. We know that, we heard that. But goddamn it’s one hell of a convincing illusion. I mean, our brains are so powerful at creating predictive patterns, anticipating the future, and maintaining concurrent thoughts like “Plato’s Republic is an interesting book worth reading” with “why is my left eye looking so weird right now oh wait THERE’s ACNE UNDER MY F*CKING EYELID WTF MAN” and all while thinking of what to eat at dinner tonight and who’s birthday it is tomorrow. Phew. So many thoughts, such connection, wow.

But oh don’t you worry don’t you worry child there’s always room for some good old FEAR, and its closest relative — ANXIETY.

OH YAS. What’s that? You’re excited for your camping trip in the woods next week? HA! But did you even obsess over the possibility of a bear eating your ass alive? There’s tons of mosquitos there, didn’t you read about the Zika virus which is transmitted through mosquito bites? Did you consider the fact that even a small cut on your foot could open up the door for lots of great opportunities like gorgeous bacteria that can make you lose your limb. I MEAN YOU COULD BE FORCED TO DRINK YOUR OWN PISS TO SAVE YOUR LIFE. (thanks Bear Grylls) You could die, It could happen to you, OH NOOOO.

Or you want to try that thing called painting but you’re afraid you’re going to suck at it? (and you probably will) Well, guess what?

1. No one gives a sh*t (make your own path)

Yep, sorry fellow human. That’s the truth. You know what keeps everyone busy most of the time? Their own thoughts, fears and anxieties. To wrap it all in a simple phrase: EVERYONE IS IN THEIR HEAD. At our core we are egotistical creatures, and (to some extent) we should be. It is part of our evolution as human species to be mostly thinking about ourselves. It is called survival.

Now, that doesn’t excuse you from being a self-entitled prick, but it does explain your biological selfish tendencies. In other words, you are an animal with selfish instincts and at the same time you have the ability to use reason to keep some of these instincts in check. This ability to moderate our instincts is arguably the most important reason of why we’re (mostly) able to cooperate, organize social structures, and build nothing less than A BUNCH OF CIVILIZATIONS while at the same time having a 99% DNA match with chimps, 98% with pigs, 97% with mice, and 1% with Gerard Depardieu’s fascinating nose.

Yes, moderation. Failing is inevitable, but don’t make it your new pornography. In other words, don’t be a masochist.

We live in the era of the social media hype. And I’m sure we’ve all seen the “influencers” trying to get your attention and motivate you to better yourself and/or buy their stuff. Personally, I’m not as cynical about them as some people, and I do believe that their (mostly) simple messages need to be said and even regurgitated sometimes; because we think we know it all but oh wow you’d be surprised how clueless most of us are at basic psychology and self-control.

There is, however, some potential danger in these influencers’ overall message, and the most common that I’ve noticed lately is the glorification of “the struggle” or “the hustle” or “the hard work”.

Yes, If I’d be to generalize, I’d definitely say that a lot of people need to struggle and need to work hard, because the majority, as Thoreau once said, “are living lives of quiet desperation” and they need a metaphorical (or sometimes literal) kick in the butt.

But what I’ve noticed lately is that some people get a high from this “hustle”, meaning that they could be working on something absolutely unnecessary or their vision might be vague or they just like to be busy and physically extenuated in order to feel fulfilled. (I can relate)

In other words, they like the hustle for hustle’s sake. The danger comes when people justify failing with “working hard”. I generally don’t believe in absolutes, and I’m a strong advocate for nuance. The fact that you’re failing and you’re still working hard is respectable, but not necessarily correct. It might be the case that you’re ignoring some of your mistakes or you’re not learning from your failures or you’re heading in the wrong direction.

Nat Eliason wrote in one of his articles about this phenomenon,

“I call this “struggle porn”: a masochistic obsession with pushing yourself harder, listening to people tell you to work harder, and broadcasting how hard you’re working.

Working hard is great, but struggle porn has a dangerous side effect: not quitting. When you believe the normal state of affairs is to feel like you’re struggling to make progress, you’ll be less likely to quit something that isn’t going anywhere.”

Gary Vaynerchuk — CEO of VaynerMedia, a full-service advertising agency servicing Fortune 100 clients across the company’s 4 locations.

So, when I hear these influencers I always take it with a grain of salt. I appreciate some of them, because I understand that some people need that “eat sh*t for 5 years and work on yourself” message. But I’m afraid that too often people take everything literally, and when they see someone like @GaryVee advocating for that, they just assume that if they do that, they’ll eventually get in a similar place like him.

You have to put things into context, and you have to be realistic; not defeatist, but realistic. That means taking someone’s advice and putting it into the context of your own life. Realize that life is not all about cause and effect — there’s lots of chaos and unpredictability. And while struggling and working hard for something is commendable, you have to be open to changing your initial expectations and adjusting your attention and direction if needed.

Looking for mentors is OK. Trying to become your mentors — is wrong. You’ll never be able to achieve it. Their philosophies and their decisions might serve you as an example and a general guideline, but they can’t be a literal road map to your life. Building that road is your personal responsibility. And that’s where failing and learning from your failures come into play.

Where I agree with Gary Vaynerchuk though is his mentality of “not letting other people’s opinions hold you back” and maximizing on your own potential and actions. In other words, letting go of things you can’t control. That is an old message, popular with ancient Stoics especially, but it is a message that needs to be repeated in this age of information overload, even if it’s over-simplified.

2. You can always try again (and you’ll usually do it better?)

The beauty of failing at something is that statistically speaking you’ll do better next time. At least that’s the general message you hear in the media. We learn from our mistakes, right?

Well, I’m here to confuse you even more. As with most things that involve the brain, it’s not that simple.

1) One study shows that we do tend to learn from our failures:

Bhanji’s team wanted to find out what strategies people use to forge ahead after failing. To test this, they brought 30 volunteers into a lab and had them play a computer game. The game modeled a classroom and the aim was for players to graduate from the class. Those who succeeded would earn $10.

But getting a player’s character to move across the computer screen and pass the class was no easy task. Along the way, players faced setbacks that could return their characters back to where they had started.

For instance, one set of players encountered an “exam.” They had to guess at the right answer to a test, pressing the right key to move forward. If they guessed wrong, they moved back to start. Another group of players faced a non-voluntary “course cancellation.” Their players, too, got sent back to the beginning of the game — but there was nothing they could have done to prevent it.

After each “failure,” players were asked if they would like to try again.

The scientists looked at activity levels in parts of each volunteer’s brain as they played. The researchers used a brain-scanning technique known as functional magnetic resonance imaging, or fMRI. It measures where blood flow is highest and lowest. An area with lots of blood flow suggests that brain region is active. The researchers looked for which brain areas’ blood flow changed when the players decided to try again.

They found that activity was reduced in some parts of the brain when players were tackling challenges. For instance, the ventral striatum sits deep in the skull and is important in motivation — such as whether to try again. Activity here dropped off when players brushed off a failure that had been within their control (such as guessing the wrong key and failing that so-called exam). The lower the activity in this brain region, the more likely a player was to give the game another go. Reduced activity in this area may not be pleasant, since it’s associated with getting something wrong. But it also is associated with learning. As they change their behavior, participants might begin to feel they can do better next time.

But when players were faced with a course cancellation — something they couldn’t control — the activity dropped in a different part of their brains. That part is located right above the eyes and called the ventromedial prefrontal cortex. This area affects how we judge risk, control our emotions and make decisions. And for uncontrollable setbacks, the lower the activity here, the more likely players were to not give up.

After a setback we can’t control, you realize that this “isn’t due to your own actions [and] you can’t correct that behavior,” Bhanji explains. And this is where successful people put more emphasis on interpreting their emotions in a way that allows them to forge ahead. So when failures are beyond someone’s control, he says, rethinking our emotional responses seems to help.

This basically means that to learn from failures is a choice. If you choose to interpret your emotions and the results of and action in a way that makes it “a lesson”, you’ll be more able to move on and improve.

2) Another study shows that some companies learn more from failure than from success:

While success is surely sweeter than failure, it seems failure is a far better teacher, and organizations that fail spectacularly often flourish more in the long run, according to a new study by Vinit Desai, assistant professor of management at the University of Colorado Denver Business School.

Desai’s research, published in the Academy of Management Journal, focused on companies and organizations that launch satellites, rockets and shuttles into space — an arena where failures are high profile and hard to conceal.

Working with Peter Madsen, assistant professor at BYU School of Management, Desai found that organizations not only learned more from failure than success, they retained that knowledge longer.

“We found that the knowledge gained from success was often fleeting while knowledge from failure stuck around for years,” he said. “But there is a tendency in organizations to ignore failure or try not to focus on it. Managers may fire people or turn over the entire workforce while they should be treating the failure as a learning opportunity.”

“Whenever you have a failure it causes a company to search for solutions and when you search for solutions it puts you as an executive in a different mindset, a more open mindset,” said Desai.He said the airline industry is one sector of the economy that has learned from failures, at least when it comes to safety.

“Despite crowded skies, airlines are incredibly reliable. The number of failures is miniscule,” he said. “And past research has shown that older airlines, those with more experience in failure, have a lower number of accidents.”

Desai doesn’t recommend seeking out failure in order to learn. Instead, he advised organizations to analyze small failures and near misses to glean useful information rather than wait for major failures.

“The most significant implication of this study…is that organizational leaders should neither ignore failures nor stigmatize those involved with them,” he concluded in the June edition of the Academy of Management Journal, “rather leaders should treat failures as invaluable learning opportunities, encouraging the open sharing of information about them.”

3) Another study, on the contrary, shows that success is way more influential on our brain than failure:

Have you ever bowled a string of strikes that seems like it came out of nowhere? There might be more to such streaks than pure luck, according to a study that offers new clues as to how the brain learns from positive and negative experiences.

Training monkeys on a two-choice visual task, researchers found that the animals’ brains kept track of recent successes and failures. A correct answer had impressive effects: it improved neural processing and sent the monkeys’ performance soaring in the next trial. But if a monkey made a mistake in one trial, even after mastering the task, it performed around chance level in the next trial — in other words, it was thrown off by mistakes instead of learning from them.

“Success has a much greater influence on the brain than failure,” says Massachusetts Institute of Technology neuroscientist Earl Miller, who led the research. He believes the findings apply to many aspects of daily life in which failures are left unpunished but achievements are rewarded in one way or another — such as when your teammates cheer your strikes at the bowling lane. The pleasurable feeling that comes with the successes is brought about by a surge in the neurotransmitter dopamine. By telling brain cells when they have struck gold, the chemical apparently signals them to keep doing whatever they did that led to success. As for failures, Miller says, we might do well to pay more attention to them, consciously encouraging our brain to learn a little more from failure than it would by default.

AND TO CONFUSE YOU EVEN MORE, here’s another study: (hahaha)

4) This study shows that we learn best when we learn BOTH from failure and success at the same time:

There have been quite a number of case studies of the after event or after action reviews that are used in the U.S. Army after training exercises, and have now been extended to a variety of settings, ranging from firefighting to corporate actions such as mergers and layoffs. The basic idea is, as soon as feasible after some action occurs, a facilitator and/or teacher should have a conversation with the key participants about what went right, what went wrong, and what could be done better next time. Harvard’s David Garvin talks extensively about after action reviews in his book Learning in Action: A Guide to Putting the Learning Organization to Work and presents some compelling cases and arguments about their effectiveness.

Shmuel Ellis and his colleagues have really dug into this issue with, first, a field experiment with two companies of soldiers in the Israel Defense Forces, who were tested for their performance on navigation exercises. The critical difference between the two groups was that — following standard practice in the Israeli military — the first company had a series of after event reviews during four days of navigation exercises that focused only on the mistakes that soldiers made, and how to correct them. The second company, in its after event discussions, focused on what could be learned from both their successes and failures.

Then, two months later, these same two companies went through two days of navigation exercises. The results showed that, although substantial learning occurred in both groups:

a) Soldiers who discussed both successes and failures learned at higher rates than soldiers who discussed just failures.

b) Soldiers in the group that discussed both successes and failures appeared to learn faster because they developed “richer mental models” of their experiences than soldiers who only discussed failures.

This study, earlier research, and a subsequent controlled experiment by Ellis and his colleagues show that experiencing failure does lead to more richer mental models than experiencing success. Consider some interesting twists from their more controlled laboratory experiments of after event reviews:

a) After people succeed at a task, they learn the most when they think about what went wrong.

b) After people fail on a task, it doesn’t matter whether they focus on successes or failures. They will learn so long as they do an after event review.

These are, of course, just two studies, but they have several interesting implications for management, assuming that the findings can be generalized to other settings:

a) After event reviews — whether focused on failure alone or both successes and failures — spark learning. Sure, you already knew that — but it amazes me how many companies don’t have time to stop and think about what they learned, but seem to have the time to keep making the same mistakes over and over and over again.

b) After people succeed at something, it is especially important to have them focus on what things went wrong. They learn more than if they just focus on success (so, don’t just gloat and congratulate yourself about what you did right; focus on what could go even better next time).

When failure happens, the most important thing is to have an after event review to provoke sufficiently deep thinking — whether you talk about successes or failures is less important.

So there’s that. Confusing, right? Well, welcome to the human brain. It’s a mess.

One takeaway for me is that when you evaluate your actions, it is wiser to consider both what you did wrong and what you did right in order to have a more complete and objective assessment of a situation.

That way, you won’t indulge into nihilism or self-pity, but you’ll be more mature. You’ll be able to analyze your weaknesses while still being proud of yourself and your accomplishments.

3. We’re all going to die

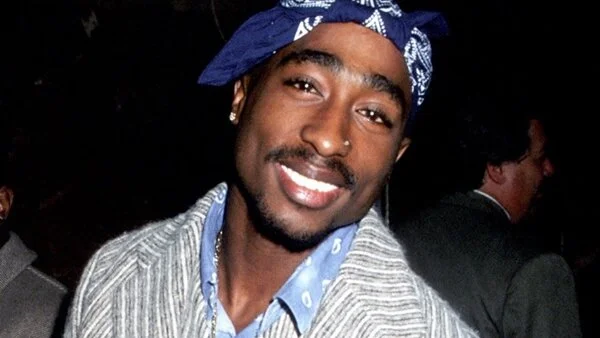

Tupac Shakur — what a handsome man he was goddamn

As the great philosopher 2pac once said,

“It’s the game of life. Do I win or do I lose? One day they’re gonna shut the game down. I gotta have as much fun and go around the board as many times as I can before it’s my turn to leave.”

It is a simple message, but it certainly does a good job in putting things into perspective. It’s basically the message from the ancient Stoics: memento mori, which translates to “meditate on death”.

“Let us prepare our minds as if we’d come to the very end of life. Let us postpone nothing. Let us balance life’s books each day. . . . The one who puts the finishing touches on their life each day is never short of time.”

— Seneca

The Stoics argued that if you’ve lived a life of purpose and meaning, you shouldn’t fear death as much, because it’s inevitable, and if anything, this fear would only stagnate your development and make you passive in your decisions while you’re still alive. Failure for the stoics is only an opportunity to learn, and the way you interpret specific failures is up to you, it’s entirely your own responsibility.

Thinking about death may be interpreted as a pessimistic outlook on life, but I would argue that it is a healthy habit (in moderation) to have, because in times of fear, before making a decision, you realize you only have so much time before it’s your turn, and agonizing over a decision for too much is pointless and unproductive.

Fail. Fail because there’s no other way. But make sure you put some effort in learning from your failures. Don’t just boast about your “toughness” and ability to live through failures — that’s not a good value in itself, it is good if you act on it, if you improve on it. Failure is an input, and a painful one at that, but it’s the only way to create some good output — healthier decisions.

But failure can also play the role of a virus which inundates your every thought and corrupts the software of your brain, making you unable to function properly, that is unless you meditate on your failures and don’t sit around waiting for miracles. That is if you act.

4. Every choice is the “right” choice

“Every path is the right path. Everything could’ve been anything else. And it would have just as much meaning.”

― Mr. Nobody (film, 2009)

The notion of right and wrong is entirely subjective to the human experience, meaning that the Universe doesn’t care, the Universe just is.

Now, that doesn’t mean that there aren’t right and wrong things, of course there are, but they are limited to us, humans, and they are not intrinsic to the Universe. And since people create these value judgments, we are the ones who impose limitations on ourselves — a thing that’s obviously necessary to organize our civilizations, but it is a thing in which we often get lost. We drown in our own anxiety.

The truth is, in most non-extreme cases, our decisions are entirely arbitrary, which means that every choice would be fine and we could adapt to most outcomes in healthy ways.

Often times just the act of deciding is more important than the actual choice we make.

Indecision tends to harm us way more in the long-term than wrong decisions. You know why? Because when we make wrong decisions, we learn the value of failing. We learn that, in some cases, if we didn’t act, and f*cked up, we wouldn’t have known how to act better.

It’s quite simple really.

Indecision = no input = nothing to learn

Wrong decision = lots of input = opportunity to learn.

Yes, there’s always exceptions, and sometimes not acting is better than doing something dumb. But see, the paradox here is that, although it is smarter sometimes to refuse to act, that sense — to use your intuition and know when to abstain — can only be developed from experience, or in other words, from failure, from lots of failure.

You get the luxury of “knowing” when not to act only when you’ve acted in the past.

And thus, we can even expand the previous equation:

Indecision = no input = nothing to learn

Wrong decision = lots of input = opportunity to learn= better ability to know when NOT to act.

And considering all of the above, psychologically (or even evolutionarily) speaking, we are conditioned to feel much more regret for the things that we haven’t done compared to the things that we’ve done wrong. It is a merciless trait that nature has “bestowed” upon us. It is basically FOMO — fear of missing out. It can destroy you from the inside. I’ve felt it in the past, and I’ve seen it in other people. The monster is real and it is relentless.

5. You’ll regret much more if you don’t act

There’s overwhelming research that confirms this statement. It’s the way we are built.

In a Huffington Post article, they mentioned a research that talked about this phenomenon:

A team of researchers at Cornell University asked people in their seventies, “What would you do differently if you could live your life over?”

Some people regretted their actions: “I shouldn’t have gotten married so young,” or “I should never have taken up smoking.”

But four times as many people described things they wish they’d done, actions they wished they’d taken.

“I should have finished college.”

“I should have aimed higher in my career.”

Or “I was too meek — I should have been more assertive.”

We think we’ll regret what we do, but most of us have bigger regrets for the things we didn’t do, when we didn’t invest our time, money, or energy.

Another research revealed even more, pointing to the same tendency:

Davidai’s latest study, conducted with Cornell psychologist Tom Gilovich, builds on a body of existing research about the types of regrets that have incredible staying power, namely those about what we could have done, not what we did do wrong. Although we experience both sorts, studies have found that across cultures and demographics, it’s regrets about inactions that haunt more of us for long periods. So you’re more likely to feel achy about never auditioning for that performing-arts school as a teenager, or never joining the Peace Corps, than you are to regret a bad real-estate move or a nightmare job that you took.

Psychologists have theorized as to why this asymmetry exists. In their paper, which was published in the journal Emotion, Davidai and Gilovich note that action-related regrets spur reparative work, which allows us to deal with them and let them go.

(Wrong decision = lots of input = opportunity to learn = opportunity to move on?)

If you missed your daughter’s graduation, you can apologize and arrange an alternate celebration. If you moved to Chicago for work and regret having left your extended family, you can vow to fly home for every holiday. But there’s usually little to be done about the goals you didn’t act on to begin with. “The one who got away may now be married to someone else; some talents can only be fully developed if one starts young; a once-in-a-lifetime job opportunity comes around only once,” the authors write.

We also process these two types of regrets differently. Selling your house at the wrong time becomes a lesson learned, or ultimately reveals a silver lining. When you miss someone’s birthday, Davidai suggests, you might spend some time questioning your motives and your relationship with that individual, because you feel guilty about having messed up. It’s hard to leave that kind of problem unresolved. However, we don’t feel the same pressure to process regrets for the path not taken, largely because the absence of action doesn’t elicit a “hot” emotional response (like anger or guilt) the way making a mistake does.

It is a painful realization — that we are going to regret more the things we wished we had done but never have. It is painful because there’s lots of things a human being wants to do in a lifetime — and there’s only so much we can do.

Our brains are meaning machines, we contemplate and think about possibilities. We can’t help it. It’s who we are.

It’s why we have art, it’s why we have complex stories. It’s why we feel like our life is a story. And it is indeed a story — a story full of joy and sadness, of pain and pleasure, of fulfillment and regret, of action and inaction, of failure and success.

Of humanity.

“If you mix the mashed potatoes and sauce, you can’t separate them later. It’s forever. The smoke comes out of Daddy’s cigarette, but it never goes back in. We cannot go back. That’s why it’s hard to choose. You have to make the right choice. As long as you don’t choose, everything remains possible.”

― Mr. Nobody

Thank you for reading! If you liked it share this article on any social network.

Take care, and don’t forget — it’s OK to fail — as long as you learn from it.