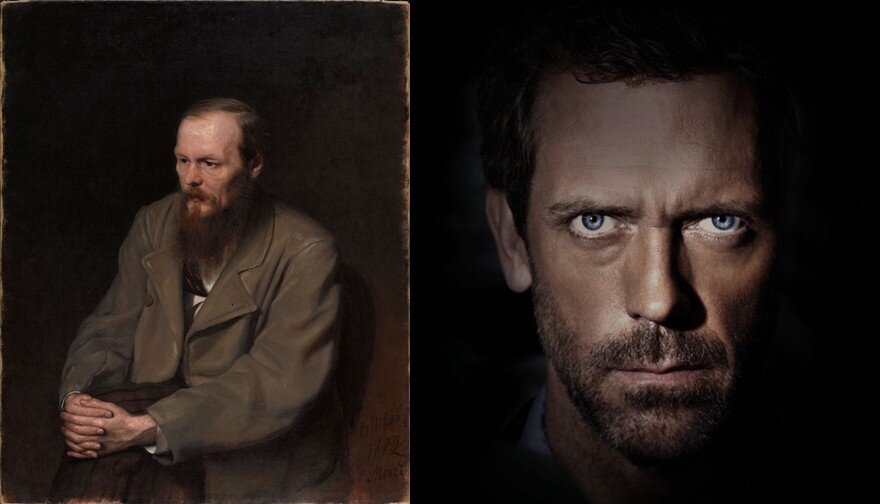

Dostoyevsky and House M.D. — Everybody Lies…To Themselves?

“Lying to ourselves is more deeply ingrained than lying to others”

— Fyodor Dostoyevsky

9 min read

If you’ve watched the TV show “House M.D.” then you’ll remember a phrase the main character (Hugh Laurie) used to always say:

“Everybody Lies”

In the context of that show it meant that his patients would often lie about their symptoms and their life background, because they felt ashamed or they tried to manipulate how they would be perceived by others, even if it concerned their life and death. House countered this with his sarcasm and his extremely cynical view of human nature.

Here’s some quotes from him:

“I don’t ask why patients lie, I just assume they all do.”

“It’s a basic truth of the human condition that everybody lies. The only variable is about what.”

“I’ve found that when you want to know the truth about someone that someone is probably the last person you should ask.”

“Dying people lie too. Wish they’d worked less, been nicer, opened orphanages for kittens. If you really want to do something, you do it. You don’t save it for a sound bite.”

This cynical quality of his character made him a very good diagnostician of complex diseases, but paradoxically, the same quality made him suffer, because the saying “everybody lies” also referred to him, and more exactly, it referred to the fact that he lied to himself and was fully aware of it at the same time.

Particularly, the most painful lie that he told himself was that he “didn’t need other people”, but as the show went on, his lack of genuine human connection had only aggravated, and he tried to fill that void with his exaggerated sarcasm and cynical view of human emotions, creating an illusory world in which he was “detached” from those emotions — which ironically only brought him more suffering, causing him to try to hurt himself because of the self-hate that he felt.

His best friend, and probably his only real friend, was Dr. Wilson — a man who was the exact opposite of House.

Dr. Wilson (left) and Dr. House (right)

In a scene from the show they had a dialogue which shows the essence of House’s character:

House: (to Wilson) “You love everybody. That’s your pathology. You’re the responsible one”

Wilson: “You know why people are nice to other people?”

House: “Oh, I know this one. Because people are good, decent and caring. Either that, or people are cowards. If I’m mean to you, you’ll be mean to me. Mutually assured destruction.”

Wilson: “Exactly….”

House: “You gonna get to your point?”

Wilson: “You need people to like you.”

House: “I don’t care if people like me.”

Wilson: …”Yes. But you need people to like you because you need people.

It is possible that House’s extremely cynical attitude towards people offered him the comfort he needed, the comforting thought that he was functioning on a higher level than human emotions and relationships. This behavior made him a master at diagnosing the pathologies of the human mind and body, but it blinded him towards his own pathology — that he wasn’t capable of sustaining healthy relationships with other people and that he was alienated from all the “mundane” activities around him. But the belief that he didn’t need people was the lie that his mind created in order to function properly, even if that lie made him suffer.

I could also make the same analogy with Sherlock Holmes and his relationship to Dr. Watson. Sherlock Holmes has similar talents and pathologies as House does, probably because the latter’s character archetype was inspired by the former. (House and Wilson = Holmes and Watson?)

So, we can be rest assured that people lie to other people, that is common knowledge. But a more painful lie is the lie we tell to ourselves. Why is it so important to study the phenomenon of self-deception?

We lie to ourselves in order to get rid of anxiety.

There are a few reasons.

First of all, lying to ourselves, as Dostoyevsky said at the beginning, “is more deeply ingrained than lying to others”. What did he mean by that?

If you’ve read at least a bit of Dostoyevsky, you would know his style of writing and the main themes in his novels. His main characters are usually troubled individuals that carry the burden of emotional pain, contradictions, paradoxes in their behavior, and an alienation from themselves, which eventually leads them to become alienated from other people.

Why would a man be alienated from himself? Dostoyevsky suggests that it comes from self-deception. But then why are we lying to ourselves? Because to confront the reality of our human condition is often an extremely painful experience. To admit that we’re not as good and honest as we once imagined, is to admit that we’re in a sense pathetic and paradoxical creatures, capable of imagining an ideal and rational world, and yet being dragged down by our primitive instincts and animal nature ruled by evolution.

Second of all, we lie to ourselves in order to get rid of anxiety.

Søren Kierkegaard — “The Father of Existentialism”

Kierkegaard, a writer from the 19th century, once said, “Anxiety is the dizziness of freedom”, probably referring to the specific human tendency of feeling anxious because of too many possibilities and choices. When we’re overwhelmed with so many options in our life, instead of feeling enthusiastic and invigorated, we often become inhibited and we hide into ourselves and into our own lies, paralyzed by the sheer number of possibilities and by the realization that we’re mortal beings that understand the real weight of our decisions. This anxiety is a core part of our human existence.

Third of all, if you read into psychology, neuroscience, and psychotherapy, you’ll find hundreds of references to the so-called “lizard brain” — which is just a simplified term of some processes from parts of our brain which originate from hundreds of thousands of years ago, when homo sapiens was a creature who fought to survive every day, in an environment in which danger was very real and imminent.

Those dangers, like predators, lack of stable shelter, extreme weather, and enemy tribes that would compete for survival — during tens and hundreds of thousands of years — formed unconscious mechanisms in our brain, which according to evolution, have allowed us to survive in spite of other species, like Neanderthals. (curious fact: some genetic studies show that most Europeans and Asians have 2% of Neanderthal DNA)

But at the same time, according to archeological findings which show that the shape of our skull has changed and was increasing in its size until about 30.000 years ago, our brains have increased in their size respectively, possibly because the regions that are responsible for cognitive, emotional abilities, creativity, and imagination, were exercised and used more often in the last few tens of thousands of years.

Therefore we now live in a type of paradox:

1.

On one hand, we have the limbic system, or “the lizard brain”, which is the most primitive part of our brain, described by neuroanatomists in 1954. It is called “The Lizard Brain” because the limbic system is about all a lizard has for brain function. It is in charge of fight, flight, feeding, fear, freezing-up, and fornication. This limbic system is mostly unconscious, therefore we can’t really control it.

2.

On the other hand, we have the paleomammalian (old mammal) brain, which includes the hypothalamus, hippocampus, amygdala, and cingulate cortex, and is the center of our motivation, emotions, and memory, including behavior such as parenting.

3.

And last but not least, we have the region that was developed most recently in the brain: the neomammalian (new mammal) brain, consisting of the neocortex, enables language, abstraction, reasoning, and planning.

This “new mammal brain” could be the possible cause of our anxiety, of our human paradox — being conscious of our intelligence, our imagination, all possibilities and ambitions…and yet at the same time, being aware of our death and decay, our primitive nature from which we can’t seem to escape, and probably, won’t be able to ever escape from.

This human paradox, of the infinitude of possibilities of our mind and our body’s physical limitations, causes us to lie to ourselves, makes us want to get rid of anxiety, to create an illusory world in which we avoid the responsibility and the huge weight of decisions in our life.

This paradox is the essence of “the existential angst”, described by Kierkegaard and other Existentialists in the 20th century. This angst is not conditioned by a predator or an imminent danger like in prehistoric times, it is caused by the realizations and anxiety of the modern man.

In this pathetic way, we then live our own self-fulfilled prophecy: that we deserve to feel bad and hate ourselves. We become alienated from ourselves and from other people, diving deeper and deeper into the psychosis of our own mind.

In his short story, Notes from The Underground, Dostoyevsky describes this type of individual — a man troubled by his own mind, suffering from self-deception and self-alienation.

In some moments, that man proves that he’s a master at dissecting the human psyche:

“Man has such a predilection for systems and abstract deduction that he is capable of deliberately distorting the truth, of denying his own senses only to justify his logic.”

“We have come to the point where the true <<living life>> is considered almost as work, almost as a job, and we all agree in ourselves that life in books is better. And why are we still worried sometimes, what are we still fooling about, what are we asking for? We do not even know what.”

“Man only counts his troubles; he doesn’t calculate his happiness.”

In other moments he expresses his hate for humanity:

“Only man is stupid, phenomenally stupid. I mean, although he’s not stupid at all, he’s so ungrateful that if you were looking, you would not find anyone worse than him.”

“I only know how to play with words, to dream so in my mind, but in reality I need … silence. And in order not to be disturbed, I would sell everyone now for a dime.”

And perhaps the most wretched and disgusting sentiment he expressed, was the vague superiority that he felt that made him despise other people, while at the same time feeling like a victim:

“I am a gadfly in front of this society, a deafening, unnecessary gadfly, more clever than all of them, more educated than all of them, more noble than all of them, but a gadfly always yielding in their way, humiliated and offended by all.”

And finally, he becomes a nihilist, a man with no morals, no ambition. A man that is not capable of differentiating between good and evil. A man that has ceased to be a man:

“You even feel that you have come to the very last place, that this is miserable, but that it cannot be otherwise, that you have no other option and that you will never become another person, that if you still had time and faith to be something else, then you probably would not even want to change, and if you wanted, you would not have done anything anyway, because in fact, maybe you do not even know into who you should change.”

“It’s not only that I’m not bad, but I really could not become anyone: neither evil, nor good, nor villain, nor an honest man, nor a hero, nor an insect.”

Notes from The Underground is a work that surprises you, amuses you, makes you curious, disgusts you, makes you relate, brings you closer and alienates you at the same time from human nature. It’s considered one of the most profound works about the human psyche and human neurosis. It’s definitely not a “fun” read. It’s tough to swallow emotionally, because it’s very cutting, intimate, and unfiltered. But it’s a very important work in world literature, and if you want to know more about this phenomenon of self-hate and self-deception, and how to avoid these bad tendencies, I’d recommend you read it.

Only by having your enemy close can you understand it better and grow capable of winning that fight — the fight with your own mind.

“Above all, don’t lie to yourself. The man who lies to himself and listens to his own lie comes to a point that he cannot distinguish the truth within him, or around him, and so loses all respect for himself and for others. And having no respect he ceases to love.”

— Fyodor Dostoyevsky, The Brothers Karamazov